This story originally ran as a three-part series in the Driftwood from Nov. 6 – 20, 2019.

Part One: The broken promise of green plastics

“Would you like a fork with your food?”

She smiled as she handed me my takeout box holding a piece of chocolate cake I purchased at an event on Salt Spring Island. “It’s compostable, so you don’t have to feel bad.”

In the server’s outstretched hand was a plastic fork with the word “compostable” embossed on the handle. Next to the table was a waste disposal station, complete with a bin for compostables. Inside was mainly discarded food amongst cardboard food trays, plastic cups, forks and knives.

Compostable plastics represent the promise of a future where we’ve fixed all of the problems associated with plastic without having to break our addiction to single-use items. I was told that I didn’t have to feel bad about using that fork. However, I couldn’t help but feel like it was all too good to be true.

When people think of compostables, they think about materials that will rot and disappear, magically turning into soil within a few months. In that way, compostable plastics are not what they seem. Compostable plastics have been touted as being part of the “solution” to waste for a long time. However, they are not the panacea they’ve been made out to be.

Some clarification in terms is needed, as the plastics we are discussing are often confusing, even for the professionals who deal with them on a daily basis.

Bio-based plastics, biodegradable plastics and compostable plastics are all completely different things, and act in very different ways after they are disposed of. Bio-based plastics are conventional plastics that are made from biological ingredients like plant starch, as opposed to petrochemical ingredients. In B.C., bio-based plastics are recyclable, according to Recycle BC spokesperson David Lefebvre, as they are essentially the same as conventional plastics.

“Biodegradable” and “compostable” are similar terms. Biodegradable means a product will be broken down into harmless particles. However, there is no time period attached to the designation, and the biodegradation process can lead to microplastics being integrated into the environment.

Compostable products need to be certified by organizations like ASTM International. They need to fit very specific standards and must degrade in an industrial facility within a specific time frame, one that is similar to other compostable items like food waste. Compostable plastics cannot leave harmful residue, and they must break down entirely into harmless particles within that time frame. Compostable products will have a certification label attached. Anything that does not have a label is not compostable.

“There’s all of these different terms that are being used, and a lot of people don’t necessarily have a great understanding of what each of those terms mean. If they don’t understand how to differentiate them, then they definitely won’t understand how they might impact the system or how we might be able to process them,” said Lefebvre.

Jack Vanderbasch, manager of the Coast Environmental composting facility in Chemainus, agrees: “That’s the pain in our asses. It’s the misconception between biodegradable and compostable,” he said as we walked through the parking lot at the facility.

Coast Environmental takes in about 30 tons of compostable materials from green bins and local businesses per day and turns it into usable compost for resale. Vanderbasch was happy to invite me on a tour of his facility, saying that it really wouldn’t sink in unless I got a first-hand look.

Central to the operation are two tented composting buildings. The first is where compost is placed in aerated piles to break down. The piles are aerated through use of a computer system and after 43 days are moved into a second tent for curing. After curing for four months, the compost is ready for resale. The compost is tested at all stages to ensure it meets health standards set out by the province. Before going to market, it goes through a sorting machine that separates out the larger pieces, which are sent through the system again. This pile is what Vanderbasch really wanted to show me.

“After it’s screened, this is all the oversized bits that come out,” he explained as we walked over. “It’s pretty much garbage, but we’ll put it though again. It’ll go through three or four times just to make sure we get as much wood product out as we can, because it’s compostable.”

What looked like a mound of blackened wood towered at least two metres over my head. Vanderbasch reached into the pile and pulled out a plastic fork. After four months of being composted at extremely high temperatures, the fork looked no different than the one I was given with my piece of cake and told not to feel bad about.

“This one says ‘made from plant-based product.’ That’s probably been in there for four months,” Vanderbasch said. “When they put the wording on there that it’s made from plant starch . . . it’s still plastic.”

As I looked at the pile, more and more plastic popped out at me. Plastic dog-waste bags, onion bags, wax-coated juice cartons, chip bags, all looking like the day they were made. Vanderbasch said that most of the wood material would be composted after a few more cycles, but eventually this pile would end up in the landfill.

“The temperatures that we get to are 90 degrees Celsius. That’s boiling water,” he said. “When it gets to that temperature, you’d think it would compost. A lot of the stuff we take disappears. It composts, it does what it’s supposed to do. Those forks will not disappear. I don’t know what the answer is.”

Vanderbasch has been trying to spread the word that plastics like these should be avoided, since the ambiguous terms make people think that everything can be composted. While some things do disappear into compost, the vast majority of the plastics he receives are in there because of a misunderstanding.

“I started going to the schools and doing seminars,” he said. “I figure the way I’m going to get to the parents is through the children. I was telling nine or 10 year olds if they see their parents putting stuff and plastic in the green bin, to tell them they can’t do that. It’s their planet.”

Provincially, there is currently no regulation that defines compostable plastics. The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy is working to include compostable plastics following ASTM standards as they update their Organic Matter Recycling Regulations. When the update comes, there could be a future for this kind of material in B.C. Compostable, bioplastics and biodegradable plastics do only make up around one per cent of the total plastic market, according to Lefebvre. But that amount is growing, and all of that plastic will need to go somewhere.

Industrial composting facilities, combined with education and regulations, may provide a solution to the compostable plastics problem for most people. However, where does that leave communities like those in the Gulf Islands, without direct access to such facilities?

Part Two: Sorting it out, a look into local solutions

I try to make it to the recycle depot at least once per week. The night before, my wife Kristen and I sit in the kitchen and sort through the week’s worth of recycling.

We try to avoid sending things to the landfill, and we also maintain a backyard composter for food scraps. Every week, as the piles of various kinds of recyclables get higher and higher, the plastics end up dwarfing the rest.

The Salt Spring Recycling Depot is operated by Salt Spring Community Services under a longstanding contract with the Capital Regional District. It is also part of the Recycle BC program. Recycle BC coordinates all consumer-based packaging and paper recycling in the province, operating on a “producer responsibility model.” Producers and distributors pay into the system, based on the amount of packaging they bring into the province.

“More than 1,200 producers are obligated under the legislation and are members of the Recycle BC program,” explained Recycle BC spokesperson David Lefebvre. “Every single one of those has to report to us and tell us how much of each individual material they’re putting into the marketplace. From that, we look at the costs of managing those materials, the revenues we get from marketing them. Then we’re able to set a fee rate based on each individual material.”

All materials, including various kinds of plastics, are distributed to central locations in the province. Plastics are sent to a company called Merlin Plastics based in the Lower Mainland. Merlin breaks down the material into the raw materials for the plastic industry, which re-uses them to make new plastic products. Only a small portion of the plastics collected in the province are sent overseas to a factory making picture frames in China. Recycle BC’s goal is to build a closed-loop system in the province to ensure all of the materials under its mandate are entirely recycled here.

Recycle BC‘s program is established based on definitions set out by the provincial government. Bio-based plastics are designed to be a part of that system. However, compostable and biodegradable plastics are not.

“If you look at your traditional compostable plastic fork, that item is actually not part of the Recycle BC program at this time. It’s not a regulated or mandated item and it does not form part of the packaging and paper that we collect. That would be considered a single-use item,” explained Lefebvre.

“Plastics that are deemed compostable can present a challenge in terms of their recyclability, and they can have a negative impact on the overall quality of the material that we recycle if they enter into the stream,” he added.

Recycle BC follows regulations set out by the provincial government. As of right now, compostable plastics do not have a government-mandated definition and, as such, the recycling industry does not know what to do with them. The government has been working on a single-use plastic plan that will help determine how these materials can be recycled, and how they can fit into the existing regimen. Until that time, there is not much that recyclers can do with the stuff.

Lefebvre explained that the compostable plastics that do end up in the stream get turned into a fuel that can be used in place of coal. While this kind of thing lessens our resource extraction, it is still a single-use solution and it produces a hydrocarbon-based fuel that emits greenhouse gases when burned.

So when a customer orders a drink served in a compostable plastic cup on Salt Spring, what are they supposed to do with their garbage? Right now, there is no good answer.

Michelle Mech is a member of Plastic Free Salt Spring and has worked to develop plastic action plans for politicians and local causes. Mech has become exasperated with the state of things on the island, and has reached the point where it makes more sense to her to use single-use plastics than their compostable alternatives.

“If you were to get a compostable cup on Salt Spring there is nowhere for it to go,” she said, adding that compostable plastics are “worse than plastics, because at least plastics can be recycled.”

Mech has been looking into ways to reduce plastic consumption on the island. She has spoken with local grocery stores, consulting on how and if to switch to compostables. Unfortunately, she describes it as a “chicken-and-egg” situation. Grocery stores here get their food waste shipped off-island to an industrial composting facility. Mech explained that one truck comes to the island per week to pick up a shipment.

“The once-a-week truck is full,” she said. “They would only send another truck if we can get it full or close to full again.”

“Compostables would be great if they could be sent to an industrial composter, but otherwise they’re not good,” she added, speaking about whether or not grocery stores should convert their packaging to compostable plastics. “It broke my heart to tell them to go back to plastic. I hate plastic.”

In 2015, the Capital Regional District banned organics from the Hartland Landfill, and since then companies have had to turn to the private sector for compost disposal.

The idea of building an industrial composter on Salt Spring has been floated for years but it has not yet happened. Based on a lack of viable options for compostable plastics, islanders have little choice when it comes to disposing of the materials. Until the provincial government comes out with its regulations and definitions, Recycle BC’s hands are tied. However, Lefebvre told me that after the regulations are public, Recycle BC should be able to integrate the plastics into their system, and have manufacturers pay the cost of recycling them.

“The challenge we have right now is that there’s no recycling solution for those materials,” he said. “The Organic Matter Recycling Regulations will hopefully provide some standards, which will then hopefully point the way towards a solution.”

Other organizations are working to solve the problem as well. The CRD is undertaking community consultation for its new Solid Waste Management Plan, which includes 15 strategies to help improve the services, including increasing organic diversion and processing capacity. An open house will be held on Salt Spring on Nov. 28 at Meaden Hall from 2 until 6 p.m. The public comment period is open until Dec. 1.

Recycling as an industry is based on a closed-loop model, or circular economy, where things that get put into the system are re-used to maintain it. While the system helps reduce raw material extraction and keeps single-use items from being wasted, a few problems do exist. Recycle BC only looks at residential recycling, not commercial. Also, items like compostable plastics can fall through the cracks in the system. A true closed-loop would ensure that nothing is wasted, and they cannot guarantee everything brought in to the province ends up in the recycling stream. Yet, Mech and Lefebvre both think this is the best option we have right now.

“If you’re looking at it from a circular economy lens, being able to recycle plastic effectively like we are here in B.C. is an environmental outcome that is beneficial,” Lefebvre said.

Mech agreed, to a point, saying that “if they’re handled correctly and we can make a circular economy out of them in the interim as we get to a more waste-free state they’re okay.”

However, as I loaded my recycling into the car for the weekly drop off, I saw a bio-based fork sitting on top of the plastics pile. I couldn’t help but wonder, why do we need so much plastic anyway?

Part Three: Finding an Alternative, Single-use solution lies outside of plastics

Imagine living without a garbage can.

Most of us probably couldn’t. I know it would be hard for me to do. Most of our homes have a can under the sink in the kitchen, one in each bathroom and one in each bedroom. Elisa Rathje got rid of hers 10 years ago.

“What I found was when I had a garbage can, I thought like it,” she told me as she was giving me a tour of her plastic- and waste-free north-end Salt Spring home. “I looked at things as though they were garbage.”

Her family’s home looks like it has gone back in time. Jars of spices, tea, coffee, grain and other staples line the shelves, a pantry filled with preserves and other scratch-made goodies have been put up for the winter ahead, and a flour mill is clamped to the counter surface. Ducks and chickens roam freely outside among the bamboo trees. They are also waiting for a big order of squash to come in, and that will sit on the porch for the winter. Rathje and her daughters dress in clothes made from natural fibres to lessen the amount of plastic they use. Even their bathroom is without plastic, with a sheet of linen for a shower curtain and refillable containers for soap and shampoo.

Despite their apparent banishment of synthetic polymers from their home, the Rathjes are not perfectly waste-free.

“I don’t love the term ‘zero waste,’ because it’s part of a system,” she said. “When I started buying in bulk I was shocked about how even they wrap plastic around a pallet. You get your things delivered, and it’s covered in plastic at the outset. Or with jars, you think you’re buying jars with metal lids, but it’s covered in plastic.”

Some of the problems Rathje mentioned were lids from milk jugs, butter wrappers and the dust that accumulates in their home. I asked Rathje about recycling, since the closed-loop consumer recycling system in B.C. is relatively environmentally neutral. Besides the time it takes to dispose of everything at the recycling depot (the Rathjes are car-free), to them, recycling should be considered a last resort rather than the first and only option.

“It’s difficult for us to see the huge amount of resources it takes to make these things. It’s just so normalized,” she said. “Any time we can just reduce the whole flow in the system is better.”

Embedded energy is the measure of the materials needed to create something. Think about how much it costs to buy a plastic fork. In some situations, it costs absolutely nothing to the average consumer, since they are handed out for free at the point of sale. Bags of bulk plastic cutlery are available for a few dollars each, with around 50 forks per pack.

What then is the cost of making a plastic fork? That question is a bit harder to answer. A typical plastic fork is made from polypropylene, which is injection moulded into the rigid shape. A database of carbon and energy used in the production of everyday materials created by former University of Bath researcher Craig Jones states that polypropylene, when it is injection moulded, uses 4.49 kg of carbon dioxide to create one kilogram of material. It also uses 15 kWh of energy to create that one kilogram of plastic. That is without counting the transportation energy, additives, colourants or packaging of the final product. Bio-based plastics do not require the extraction of oil as a base material, but plant-based alternatives do require farmland, pesticides, energy and transportation, and are often used only for a short period of time like their synthetic cousins. For comparison, plastics in general use 3.31 kg of CO2 per kilogram. Nylon, which makes up most synthetic textile fibres, uses 9.14 kg of CO2 per kilo, and high-density polyethylene, which is used to make most packaging, uses 2.52 kg of CO2 per kilo.

Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh found in 2010 that during the manufacturing process, green and bio-based plastics generally were worse for the environment than synthetically derived ones. The research team attributed agricultural fertilizers, pesticides, land use and chemical processing to the large impact of the plant-based products. However, once manufactured, the bio-based plastics were much more eco-friendly than their synthetic counterparts.

If plastics of all kinds take this much work to create, and are generally thrown out after their first use, I wondered: Why bother to use them at all?

Plastic is a relatively recent invention. The late 19th century saw multiple polymers developed, and in 1907 the first fully synthetic plastic was created.

When Nina Raginsky, a retired photographer living on Salt Spring Island, was growing up, there was almost no such thing as plastic. She was born in 1941, the same year polyethylene terephthalate (PET, the plastic used in plastic water bottles and eventually synthesized by bacteria into bio-based plastic) was invented. As plastics took off in the post-war years, Raginsky was early to resist the trend.

“I don’t know why I didn’t want plastic,” she said. “All of a sudden there was a plethora of it, because everybody wanted it. It’s so recent . . . I raised my daughter with no plastic. She couldn’t have plastic dolls or anything. She’s 40-something now. Even before then I had no plastic.”

She did, however, concede to using small amounts of plastic in the early days.

“I had a bakelite telephone,” she remembered.

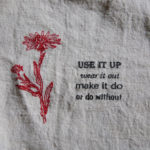

Raginsky’s home is much like the Rathjes’. Her furniture all dates back to the 1960s or earlier, and she would much rather fix something than throw it away to buy a new one. She excitedly showed me a towel imprinted with a saying that would become her motto: ‘use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.’

“It’s like the art of making do,” she explained.

Looking around the room, it was clear that it truly was the art of making do. As I had noticed at the Rathje home, things made without plastic simply looked better than plastic alternatives. A collection of plastic-free containers looks clean, orderly and beautiful. Replace those items with plastics and it looks like garbage. Both Rathje and Raginsky said that the move away from plastics forced them to look more at quality, since nothing could be purchased to simply throw away.

“I really like how beautiful things are when there’s no plastic. It’s an instant shift. Things are nicer looking without plastic,” Rathje said. “What you did before [was buy a good quality boot] and resole it and keep it going for your whole life. That would be nice. I would happily commit to something. I’ve been wearing my coat for 11 or 12 years. Now I look at it and think ‘I would buy that vintage.’”

“Why don’t you bring your own fork? We all used to do that, back in the ‘60s,” Raginsky agreed.

I am not at the point where I can live without a garbage can. I am working on it, though. I bring a travel mug with me when I want a coffee, I buy whole foods when I can, I recycle what plastics I use, and I avoid compostable plastics, since I can’t deal with them appropriately where I live.

I usually carry my own cutlery around with me too, except for the night described at the beginning of this series when I was given a supposedly “compostable” fork . . . that wasn’t.